I have long been searching for the best way to describe what it is that I want for my hometown, the City of Cleveland. Some have framed the mission I take on as one to "save" the city; others criticize this goal as a reinvention that neglects the past. I believe that the right goal, the right mission, is that of revival. We need to bring Cleveland back to the level of importance it once held. During the first half of the 20th Century it was the fifth largest city in the United States and home to industry, affluent society, and massive economic activity. We cannot achieve that by following the playbook of 19th century America, but we also cannot allow our city to tear apart it's heritage and past in order to stage its future. The challenge facing new-urbanists and the policymakers in our cities is to balance the needs of the present with the goals of tomorrow and the infrastructure of our past. This country no longer needs a city whose horizon is populated with smokestacks channeling out the heat and soot from steel mills. Instead, America needs creative problem-solving citizens: entrepreneurs who can create the 21st century's new jobs and engage their fellow citizens with a new purpose and niche to fill. Both Cleveland and the American City need a revival.

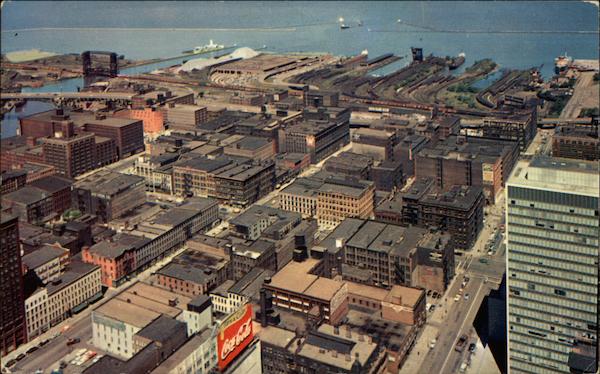

Recently, I came across a series of photographs of Cleveland from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The photos were from a forum of dedicated urbanists who love the city. Posts followed each photograph expressing a sense of longing and, at times, anguish over seeing the glorious old images. One in particular showed the Warehouse District (WHD) of Cleveland, an area of roughly 50 acres just west of downtown's public square. The district was filled, block -by -block, with brick and stone warehouses, each with beautiful facades, window frames, doorways, and various other masonry details. On foot, one can only imagine that, the roads of the WHD offered dense and vibrant streetscapes. Its sidewalks were likely full of pedestrians, moving from offices to local coffee shops, dodging streetcars along the way.

Today the WHD is home to only a fraction of these buildings and more than half of the land has been converted into surface parking lots. The activity, vibrancy, and synergy of workers and residents has been lost to a veritable ocean of asphalt.

This is one of many stories that have impacted the social and economic landscape of Cleveland. Once, the fifth largest city in the United States, Cleveland now struggles with a shrinking population and the echoing repercussions of white flight, suburban sprawl, and of carving highways through and around the region.

But can the city come back? Over the last two decades, Cleveland has seen a variety of signs that its streets have yet to be drained completely of life . Public-private partnerships have funded numerous large building projects, including three stadiums, the nationally renowned Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum, and a pioneering Convention Center/Medical Mart combo in the heart of the city, which is currently under construction. Shift to a higher powered lens and you'll see smaller, but possibly more important, projects underway. Developers have energized a corridor known as East Fourth into one of the top entertainment areas in downtown while hundreds of millions of dollars have gone into various projects around the University Circle, or Uptown, neighborhood.

But a full scale revival of Cleveland is far from upon us. The institutions that can perpetuate, or destroy, the energy of a city are manifold and they must be examined individually but understood holistically as well.

So this blog, in brief, is going to be a history of the things I learn while searching for keys to the revival of my hometown. I'll be posting various notes and findings from books on infrastructure, finance, economic development, urban planning, architecture, and just about everything else you can imagine. Though I don't expect to find a panacea for the city, I do believe that best practices exist, and by pulling together various notes and looking for synergies, I expect to find answers to my questions.

No, that's not New York City. Above, Euclid Avenue in the early 20th century.

Cities are imperfect. They are organic centers of human development and are able to magnify our greatest successes as well as our most horrifying failures. They are the peak of human achievement and represent a possibility that is only real when society comes together. Cleveland's story is not unique. The advent of the car and the age of highways and suburbia has taken its toll on every major city in the United States, but the oldest and most storied successes of America lie in the rust belt cities that, today, barely echo their former glory. A revival of their downtowns and city centers would bring about a return to the city, an economic boost that would generate the innovation and creative entrepreneurship this country needs. The pulse of life in the streets of a city can be felt throughout its entire region, and the successes of that city are reflected in the quality of life and quantity of opportunity for its citizens.

Cleveland's revival could be America's revival. So let's begin...

No comments:

Post a Comment