You get a parking lot! And you get a parking lot! And you get a parking lot! …man I love Oprah. But in all seriousness the way some of our nation’s downtowns look today one would think surface parking lots were being given away. Like an invasive species they have crept into the cityscape, expanding and taking over lot by lot, block by block, until entire neighborhoods consist of a sea of asphalt with an occasional island of structure.

So how did this happen? How did the surface lot become a ubiquitous part of the urban landscape? To understand this we must go back to the time before they ever existed, before the car.

Mainstreet used to be a real place, not just a nostalgic term used by politicians. Cities had grids of streets branching out from an original artery of commerce often named “Main Street”. The main form of transportation was by foot and thus homes and businesses were built as closely as possible. In this form the city was a dense grid of roads and businesses with no space dedicated to transportation. As streetcars became more affordable cities built lines into the roads and connected the various mainstreets to a network. This transportation system would allow cities to expand while maintaining dense land uses. People still wanted to be close to their work or at the very least close to transit stations, and as such areas of higher density built up along the transit routes and cities’ cores grew more dense and vibrant.

Public transportation is, in essence, the natural progression of movement in a city. Take for example a city in the mid-19th century. Horses, at the time, were the individual’s form of transportation, however they were expensive and difficult to maintain in an urban environment. This is why we did not see open fields for tying up dozens of horses built alongside commercial buildings in New York or Chicago. When public transportation became possible it represented a new piece of society. Much like utilities and roads, street cars were a part of the built environment and were fixtures of the city’s infrastructure. They were available to everyone and facilitated movement between the jobs and homes of citizens. Cars offered a similar payoff, but with a much steeper cost. Every form of transportation requires roads; pedestrians, cyclists, bus riders, car drivers, and light rail riders all require that roads and paths exist between the elements of the city. However, cars required additional area to be allocated to the car and, thus, parking lots were born.

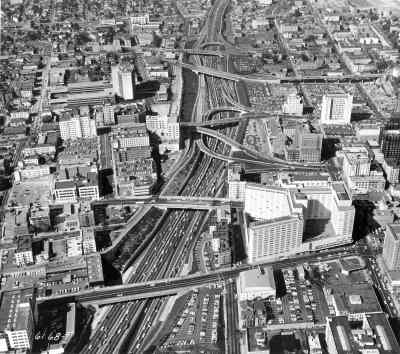

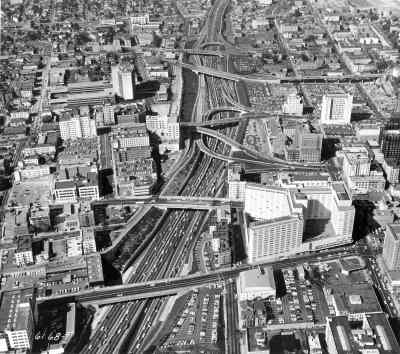

As the car became more popular companies saw a need for parking infrastructure and built single-use parking lots wherever possible. As the economies of cities continued to grow into the 1950s most cities cut their public transportation services and removed their light rail infrastructure allowing cars to take over as the main method of moving citizens. But as highways were paved through our cities the flow of goods and people moved just as easily into the city center as it did move away from it. Firms began building their offices further away from the city and people and industry fled. Many landlords saw their tenants leave and with little reason to suspect the economic circumstances to change for the better had to consider alternative uses for their land. At this point it’s important to note that cities often determine property taxes based on the value of the land which includes infrastructure whether or not it is vacant. As such there was a disincentive for landowners to maintain their buildings and many beautiful old buildings were demolished and lost forever because of this. The empty lots were easily turned into parking space and the abundant parking made for cheap rates and perpetuated the car culture. Lastly an empty lot poses a bigger challenge for redevelopment than an old building. Repairing and repurposing old warehouses and commercial buildings into lofts and unique commercial space is very trendy today and yields strong returns to investors. However, building a new structure from scratch is more costly and, of course, lends no historic value.

Without an efficient public transportation option the car became the best method of moving around, or more appropriately into and out of, the city. As such, parking lots became staples of the new city filling in every gap left by demolition. The avenues that used to be walled in by store fronts, apartments, and office buildings became host to vacant buildings and open lots; they were deserted at night.

Today many of America's downtowns are covered in patches of black asphalt and to lend insult to injury many of these empty blocks used to support historic buildings complete with architecture that we will likely never see again. This type of land use, the lowest density possible with only a single allowable purpose, is the antithesis of what a city needs. The patches hurt the walk-ability of a city by creating gaps in the streetscape that increase distances between points of interest. The further apart things are, the less likely people will be willing to go between them. This, in turn, inspires others to use cars and drive between these places. It is a self-fulfilling prophecy that by making singular places more accessible by car we in turn become more reliant on the car to get us there.

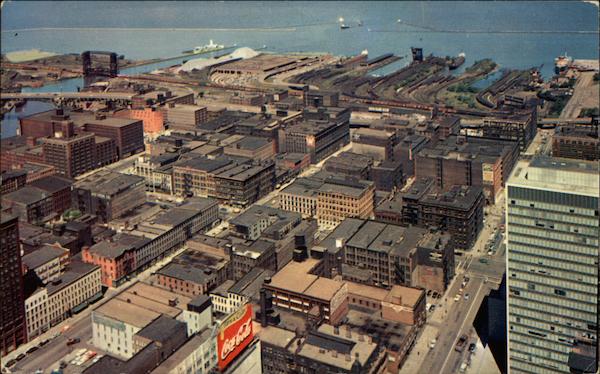

This kind of feedback loop runs counter to those which make the city vibrant and energized and instead serve to expand sprawl and destroy the dense and complex fabric of an urban environment. Cities must take steps to mitigate the presence of surface lots. Parking garages must be encouraged whenever possible, public transportation options must be enhanced and expanded, and taxes must be revised as to not penalize landowners who maintain their vacant buildings. If we could simply restore the empty buildings throughout downtown Cleveland, the current interest developers have in re-purposed units would make them much more attractive than surface lots.

Like a web, the city requires all the strands and connections to maintain its strength. By slowly removing buildings we not only lose parts of the web, but lose the connections these places made. The loss of a bank, tailor, or department store hurts the residents who live nearby. The loss of those residents subsequently hurts other commercial ventures and the decay continues until the web falls to pieces.

Public transit systems enhance the flow of people within a city and amplify its energy. Personal transit systems expand the flow of people into, and subsequently out of, the city, and dampen its energy. The surface parking lot is a symptom of the disease of car culture, and the more you see in a cityscape the more troubled the story. If a city is a beautiful pattern of interwoven activities, the parking lot is a dramatic blemish on the fabric.